What is an organism?

It’s not an easy question to answer. When faced with such a challenge, it is natural to employ metaphors that help us formulate some preliminary ideas about what it is we’re dealing with. These metaphors relate something that is mysterious to us, like the organism, to one that is well known to us, such as the machine. We know what machines are, and generally how they function, and so this metaphor gives us a point of entry into the analysis of organisms. What are the organism’s parts? How do they interact? When the organism breaks down, what parts must be repaired or replaced? Where does the energy come from that makes it work? And so on and so forth.

The challenge in our reliance on metaphors is that they can limit our understanding as easily as they can expand it. When faced with a subject as tantalizing as the study of organisms, the metaphor can preclude us from noticing essential qualities of their structure or organization, because the map, in its usefulness, inadvertently becomes the territory. It’s not that we don’t recognize these differences—we know that machines do not repair themselves, grow, or reproduce for instance, while organisms do—but there is a tendency to insist the metaphor still holds. A sufficiently complex machine, for instance, might very well do these things. And so we can continue to classify the organism as a machine, albeit an especially profound one, and then continue our search for mechanisms that underlie its various functions. The result can be misleading: the conflation of machinery with life itself, or the reduction of life to apparatus alone.

Machines as we know them today are still rather brute devices that rely on simplistic physical and chemical relationships. Cranks, pulleys and shafts convey forces. Fuel and oxygen combust to release energy in confined spaces. Electricity and magnetism are channeled through tiny circuits, or harnessed to produce linear or rotary motion in subassemblies. And we can do amazing things with this toolkit. But we cannot explain organisms. What if the machine model obfuscates fundamental questions about organisms that might lead to new insights? To what then, might we compare life, if not a machine?

In Mae-Wan Ho’s book The Rainbow and the Worm, she shows that other metaphors of the organism are equally relevant—the jazz band, the liquid crystal, and the rainbow, among others. She focuses on the intersection of twenty-first century physics with modern biology to show that organisms are at least as advanced in the mechanisms they deploy as our present understanding of the natural world allows us to comprehend.

There are two key aspects of biological systems that Mae-Wan highlights. The first is that life exhibits a comprehensive dynamic order at the quantum scale, which none of the machinery we know today does. Quantum mechanics has certainly played a vital role in our technological progress, and is essential to such technologies as GPS, satellite communications, smartphones, computers, and magnetic imaging, but it is not the case that the comprehensive atomic structure of the physical devices we use everyday is contingent upon these functions. For a few discrete subsystems or subassemblies it may be, but for the bulk of the material in a manufactured object, the dynamic interrelationships of the atomic structure are irrelevant to the object’s core function. The classical properties alone are sufficient. This is not the case with organisms.

Quantum mechanics is known today for its spookiness, but at its foundation it resolved a couple of key questions that classical mechanics could not. It’s worth noting that none of these early breakthroughs were based upon the head-scratching quantum mechanics that receives most of the press these days. They were based on the idea that energy, matter and light exist in minimum, discrete quantities. Two key challenges of classical theories that were resolved by this realization were the so-called ultraviolet catastrophe and the mystery of the electron’s orbit around the atom.

The former is the theoretical prediction that the radiant energy emitted from objects at high temperatures should approach infinity, but it does not. The reason is the quantum. With regards to the latter, in classical mechanics the electron should emit electromagnetic radiation as it flies around the atom, causing it to lose energy and crash into the nucleus. But it doesn’t. The reason is that quantum physics only allows electrons to occupy specific orbitals, and they don’t lose energy by zooming around in a given orbital, only by changing orbits, which means atoms don’t arbitrarily collapse.

It turns out that the structure of living organisms is entirely dependent on these aspects of quantum physics. In contrast to systems of relatively disorganized molecules like chicken soup, the atmosphere, or the water in the sea, organisms store a considerably higher fraction of their energy in bound quantum states. By the latter I mean atoms linked together by stable chemical bonds that store a great deal of energy, but are stable because of the quantum physics described above. Life stores energy in molecular trapdoors for later retrieval. Machines do not do this.

Mae-Wan notes that if all of the energy contained in living organisms were converted to thermal energy—as opposed to the electronic form in which it is actually stored and utilized—the human body temperature would be upwards of 3,000 degrees Kelvin. To put this in perspective, the surface of the Earth is about 288 degrees Kelvin, and the surface of the sun about 5,780 degrees Kelvin. Thankfully for us, we are not the thermal engines we thought we were.

Related to this, not only do organisms store energy electronically, they use it electronically. Living organisms utilize energy with close to 100% efficiency when transforming it from one form to another. This is remarkable when one considers that the electricity grid of an industrialized nation operates at about 40% efficiency, plus or minus, when converting the stored chemical energy of fossil fuels to delivered electricity. (Renewable electricity systems are even less efficient, though efficiency is not really a meaningful metric to apply when comparing them to fossil-fuel based technologies.) The chemical energy of hydrocarbons such as oil and natural gas is in many ways similar to the stored energy in living cells—the energy is contained in the stable bonds that link one atom to the next to form large structures of carbon and hydrogen—but our industrial processes come nowhere close to the efficiency of living organisms in converting such energy into actual work. As organisms, we move our muscles, breath, digest food, sing opera, and think with essentially zero energetic waste. It’s not that organisms don’t use energy. They do. But unlike machines, they use it one quantum at a time.

A second key element of Mae-Wan’s synthesis in The Rainbow and the Worm is long-range order, or coherence. This is a slightly complicated subject in that coherence is a word that could have both classical and quantum physics meanings, but the essence of the two is very similar. Classical coherence is the condition in which a system of oscillators share a common phase. You could imagine several tuning forks, each with the same natural frequency. If you struck them all at roughly the same time, they would each ring with the same tone, but due to inherent variations in when you actually struck each one, they would not initially be in phase. Over some period of time, however, because the energy they exchange with one another through sound waves impacts their vibrations, they would settle into a condition in which they not only rang with the same tone, but did so in phase.

Quantum coherence is more difficult for me to distinguish or fully understand, but real world examples are lasers and superconductivity. In a laser, the light emitted from a large population of atoms is the same frequency, and, like the classical definition above, is completely in phase. This is because all of the electrons that are changing state to emit the light are undergoing a transition from the identical high energy orbit to the identical low energy orbit in their respective atoms. The light they each emit is thus of the same frequency. In a laser, there are mechanisms in place to “pump” the system which results in a synchronicity of the light emissions. (Interestingly, Mae-Wan notes that the organisms may utilize metabolic “pumping” for similar purposes in the body.) Superconductivity occurs when electricity can be conveyed through a conductor with zero resistance. This also is related to a global phase relationship in the electrons within the material. This type of coherence exists at the quantum scale, but is quite similar to the classical coherence described above.

But in the quantum world there is another sort of coherence, and this occurs when various possible states of a system are in phase. This is where we get into the spookier realities of quantum mechanics, in which, for instance, one atom or electron can be said to occupy multiple states simultaneously. This state is a coherent one, because all the possible states are in phase, and it is only when we make a measurement, or when the system otherwise interacts with the environment, that a particular state is selected. It does this by “de-cohering”, or breaking phase with the other possible states. It is this type of coherence that we are attempting to leverage in quantum computing. I believe it is this type of coherence that has been observed in the photosynthetic systems of organisms.

I think the important aspect of this topic overall is what coherence affords to the systems in which it exists. Mae-Wan points to several salient features of coherent systems. She writes, “Coherent excitations can account for many of the most characteristic properties of living organisms that I have drawn your attention to at the beginning of this book: long range order and coordination; rapid and efficiency energy transfer, as well as extreme sensitivity to specific signals.”

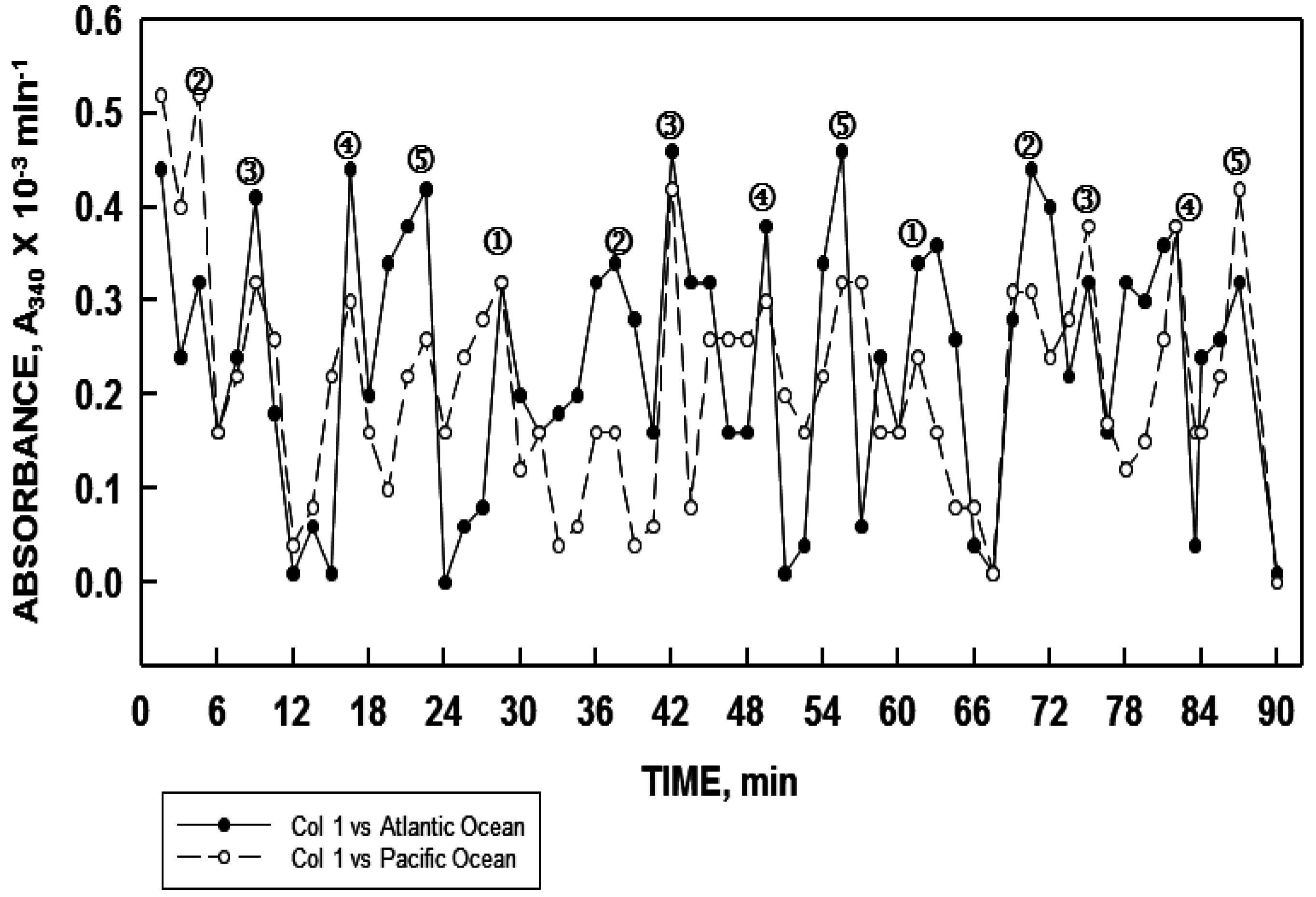

A couple of key examples Mae-Wan uses are the sensitivity of the human eye to an individual photon, which relies on the amplification of the signal by thousands of receptors with virtual simultaneity, and the processes associated with muscle contraction, in which billions of molecular operations per second are carried out with perfect coordination. With regards to the latter, she cites an experiment in which the energy from individual ATP molecules was utilized by four cycles of cross-bridge formation between actin and myosin—the fundamental, repeated action associated with muscle contraction. How could the energy from one molecule be shared over four individual cycles? Through coherence, she says, which allows for multi-mode storage and transfer of energy in both space and time.

This is where the jazz band analogy comes into play. Various members of an ensemble may depart temporarily from a common beat, but after enough measures there will be a return to the original “heartbeat” of the piece. The jazz band metaphor is about multiple rhythms occurring simultaneously without loss of the overarching unity that forms the whole. In the example of the muscle contraction, energy is dispersed over all of the various modes of the system, which allows it to be used in non-linear ways.

This might all sound like science fiction, but there is beautiful physical evidence for this idea. Using a microscopy technique known to reveal the crystalline order of various mineral specimens, Mae-Wan and her collaborators showed that the molecular structure of living tissue exists in a liquid crystalline state. The molecular order of this state is visible as dynamic bands of color within the living tissue—colors that are visible because the tissue exhibits the property of birefringence (which it loses quickly when the tissue dies). The images on the cover of her book below were developed using this microscopy technique. Speaking of this discovery, she writes, “The colour generated and its intensity (the brightness) depends respectively on the structure of the particular molecules (the intrinsic anisotropy of the molecules) and their degree of coherent order.” (Emphasis contained in the original.)

So what is an organism then? Who knows!? What we can say is that unlike any machinery we’ve invented to date, it is a self-directed energetic structure of nested, multi-modal order. It is something like a symphony, or a jazz band—a dynamically evolving wholeness in which each part is an integral expression of the wholeness itself. What I love most about The Rainbow and the Worm is Mae-Wan’s demonstration that our understanding of life is limited only by our imagination…